/ Conversation

Architect Vo Trong Nghia meditates on creative process

By Patrick Hartiga, for The Saturday Paper, 21 October 2016

Nature and the interdependence of all things are the keys to architect Vo Trong Nghia creations.

The day after meeting Vo Trong Nghia I declared to my wife that I planned to attend a 10-day vipassana meditation retreat. Her tilting head indicated cautious support for the idea. Then, remembering my lower back issues, she sensibly suggested I ask my yoga teacher about whether, in her opinion, I could physically get through it. I sent a text message to Nghia later that night to thank him for our conversation. His reply caused a tiny, freshly discernible spot fire of anger: “Please go and meditate in Blue Mountains soon.”

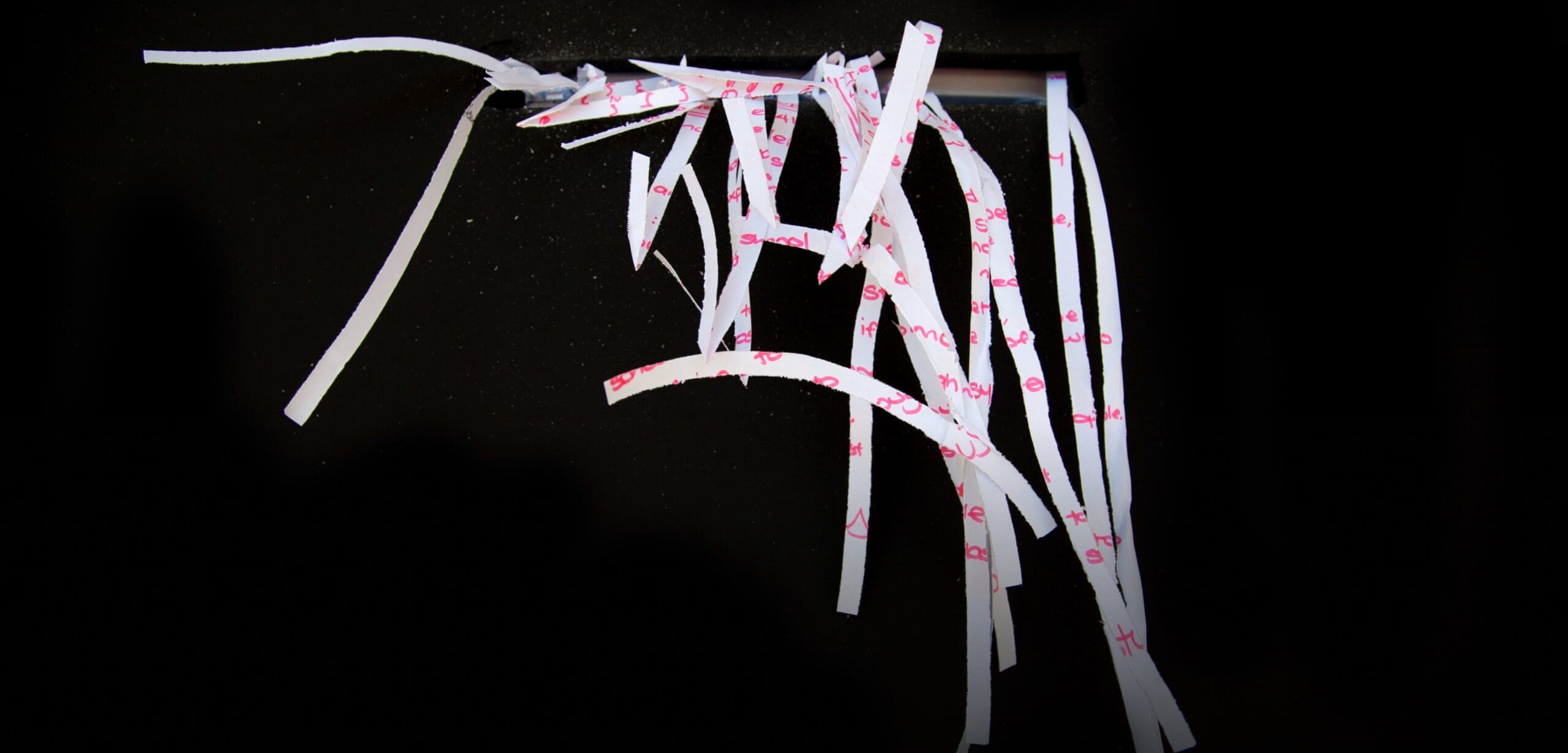

Nghia returned again and again to the importance of meditation during our chat at the Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation in Sydney, where his Green Ladder will be up until December 10 as the latest Fugitive Structures series of architectural commissions. The discipline of meditating at least two hours a day in the Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City offices of Vo Trong Nghia Architects was initiated following Nghia’s own 10-day vipassana retreat in 2012.

Vipassana meditation dates back to the writings of Burmese monk Medawi (1728-1816) and is designed to draw attention to what in Buddhism are known as the three marks of existence: impermanence, suffering and non-self. All 80 of the architects working for Nghia are paid to attend a vipassana retreat, in which there is no talking, before incorporating a mandatory two-hour meditation session into their working days.

The mark left by prolonged periods of silence was palpable in Nghia, who sat before me with a sturdiness and calm reminiscent of the scaffold of bamboo glistening in the gentle rain directly behind him. The charred shoots of bamboo forming Green Ladder are pegged together in a criss-cross formation. Bamboo, the material that peasants and farmers have most relied on across Asia, is an exceptional building material: fast growing, light, both incredibly strong and flexible.

Washing and curing bamboo avoids it becoming brittle when charred over an open fire; the latter results in the pleasant aroma I breathed as I talked to Nghia. In front of me I see the tiny holes, out of which the starch and sugar is drained, revealing the curing process key to making this material long lasting. The man in charge of curing the bamboo for Nghia also adheres to the rigorous schedule of meditation. “Before he was really bad: drinking and fighting,” Nghia explains while jabbing the air with his right fist. “But now he has become super calm.” Nghia is a champion of bamboo and meditation; an array of recent projects transform peasant necessity, and in some ways national trauma, into works of spectacular grandeur and public healing.

At different points in the conversation Nghia clasps his chest when referring to the pain and anger he had lived with before arriving at meditation; it made me think of the “curing” process of the bamboo – also needing to be “cleaned out” in order to function effectively. His ideas brought to mind the life and work of a Vietnamese monk, Thich Nhat Hanh, whose teachings Nghia has read. In the 1960s Hanh developed a socially “engaged Buddhism”, which led to his followers going out into the countryside of Vietnam and helping populations devastated by the war rebuild their homes.

Hanh emphasised the “interdependence” of all phenomena; in bringing to mind a table he asks us to consider “the non-table world: the forest where the wood grew and was cut, the carpenter … the parents and ancestors of the carpenter … the sun and rain which made it possible for the trees to grow”. Nghia’s approach to both architecture and the running of his company recognises interdependence as an essential foundation. Hanh also pointed out that “people have a hard time letting go of their suffering. Out of fear of the unknown they prefer suffering that is familiar.”

In Nghia’s case the suffering he managed to let go of links back to his childhood years growing up in a region devastated by the impacts of the Vietnam War. Born in 1976, a year after the Fall of Saigon, now Ho Chi Minh City, and the conclusion of the war, Nghia’s playground was the minefield of Quang Binh – a 40-kilometre wide strip of land between North and South Vietnam that became disastrously exposed to B-52 bombing campaigns. “My mother and father lived under the bombs of America,” he explains, making broad sweeping arcs with both his arms to describe the “mountains” of explosives left in the fields where he and his friends played. While the mountains might have gone, children to this day are killed by the mines planted by the United States army in their attempts to prevent the North Vietnamese forces pushing south. It’s this lush, green arcadia infected with war that provides the backdrop to Nghia’s ambitions as an architect.

Many of Nghia’s projects, including a conference hall, community centres, wedding venues, a low-cost prototype aimed at meeting the housing crisis facing Vietnam’s Mekong Delta area, and a farming kindergarten built beside, and providing food for, a shoe factory where the children’s parents work, reveal his interest in fostering community. Other projects take on the challenge of “greening the city”, of encouraging harmony between people and their natural surroundings by combating the concrete jungles of Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City with plant life and biodiversity. In Ho Chi Minh City construction is under way for a 22,500-square-metre campus for the private technology-focused FPT University. So camouflaged will it be by plant life it might easily be mistaken for a forest from overhead. According to Nghia’s firm, the campus will provide an “undulating forested mountain growing out of the city of concrete and brick”.

Taking in Nghia’s green visions while scrolling through Google images – some, such as the above-mentioned, still in the form of digital renderings rather than actualities – grants a glimpse of this utopia but also of the apocalyptic flip side conjured by his projects: human structures without their human inhabitants, overgrown and penetrated by an insouciant nature.

“Human beings are just a small part of nature … really, really, really, really small,” Nghia stresses to me, bringing his forefinger and thumb to within a hair’s width. It was a gesture in keeping with the opinion of climate scientists on our chances of survival, and Nghia’s project would appear to be one of having nature fight back before its human settlers are left without enough clean air, let alone air-conditioning.

Green Ladder meanwhile incorporates nature more subtly and austerely. Bougainvilleas in bamboo-clad pots punctuate the uniform and lean structure with an inflection reminiscent of the practice of Japanese flower arranging, or ikebana, while sitting on the unlit porch overlooking the flower rack brings to mind the slow cinematic scenes of Yasujirō Ozu. Nghia has a close association with Japan: prior to opening his practice in 2006 he spent seven years completing his studies in Tokyo and Nagoya, and is now a visiting professor at the Hiroshima Institute of Technology. When I ask him about the influence Japanese culture might have had on his work he points to the exacting standards of Japanese craftsmanship. The way he talked about the intensity and tenacity of Japanese building practices, his hands chiselling the air, reminded me of a scene I once stood transfixed by in a Tokyo subway station. Beneath a frenzy of human conveyance and automated sing-song instruction, I found a kneeling man monkishly devoted to the task of scraping gum off the tiles.

Nghia courteously laughs off his reputation among many of his fraternity in Vietnam, where people sometimes say, “Go to Mr Nghia’s office and you will become a monk.” His new Ho Chi Minh City office sounds very much like a monastery. Surrounded by vegetable gardens – a vertical garden that is, in the tradition of Stacking Green (2014), a house he designed in the same city – from which the staff can feed themselves, there are rooms for both meditation and yoga.

According to Nghia’s example, both architecture and meditation can bring humans to their senses, allow humans to not take themselves – their each and every breath – and the world they live in for granted. This doesn’t deny the role of experimenting and learning, Nghia explains, but simply creates the space required for new ideas to emerge: calm the mind in order to climb the ladder of our knowledge more effectively, more clear-sightedly. “Ninety or 95 per cent of thinking is unnecessary,” he says. “It’s super hard for humans to stop thinking, but suddenly your mind becomes really calm, really quiet, and then the idea comes out.”

In discussing his creative process, of arriving at material solutions by stepping off the treadmill of endless conceptualising, Nghia uses the analogy of a moon reflecting in water: when the waters of the mind are calm we see the moon’s reflection perfectly. The image of a lake with a moon in it brought a little dog bolting across the screen of my mind’s eye; I later remembered the fable from my childhood about the dog that jumped into a lake, and presumably perished, thinking that the moon’s reflection was a wedge of cheese. My mind briefly flitted between the moon as a symbol of clarity on the one hand, and greed on the other. The two qualities would seem to be related in Nghia’s experience. “This kind of economic system is no more good,” he insisted “… Living with less is better, no more attachment.”

The dimensions of Green Ladder bring the plight of some of modern society’s victims to mind, by way of the makeshift structures aboard which asylum seekers risk their lives to get to more stable shores. But this structure is all about stillness and the longer I sat breathing in its smoky aromas while talking with Nghia, the more I understood it as a shrine, a humble offering of material integrity and sensory pleasure.

The buildings Nghia brings to life tackle the challenges of promoting harmony between people and between people and their natural environments. “Otherwise we are going to be really crazy … or we’re crazy already!” he laughed. I nodded in agreement, alarmed by eyes so sure of this predicament while utterly convinced by their equanimity. “Why don’t you do a course of vipassana in the Blue Mountains?” he offered before heading off to his next interview. “You will write better after that.”